Parental Heart Failure May Become a Family Affair

FRAMINGHAM, Mass. -- Children of parents who develop heart failure appear to be predisposed themselves to both left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and overt heart failure, researchers here reported.

FRAMINGHAM, Mass., July 12 -- Children of parents who develop heart failure appear to be predisposed themselves to both left-ventricular systolic dysfunction and overt heart failure, researchers here reported.

In a cross-sectional analysis of 1,497 participants in the Framingham Offspring Study, parental heart failure was associated with almost twice the likelihood of left-ventricular systolic dysfunction in their offspring, according to a report in the July 13 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prospectively, there was also at least a 70% increased risk of heart failure, after adjustment for established risk factors ,said Ramachandran Vasan, M.D., of the Framingham Heart Study of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, and colleagues.

In an analysis of participants in the Framingham study (mean age, 57 years; 819 women) who underwent routine echocardiography, 1,039 participants whose parents did not have heart failure were compared with 458 who had at least one affected parent.

Compared with participants who had unaffected parents, participants with at least one heart-failure parent were more likely to have increased left-ventricular mass (17.0 % versus 26.9%), increased left-ventricular internal dimensions (18.6 % versus 23.4%), and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (3.1% versus 5.7%.

The multivariable-adjusted odds ratios were 1.35 (95% confidence interval, 0.99 to 1.84), 1.29 (CI, 0.96 to 1.72), and 2.37 (CI, 1.22 to 4.61), respectively, the researchers said.

Among women, 2.7% of those with heart-failure parents and 1.1% of those with unaffected parents had ventricular systolic dysfunction. Among men, the corresponding figures were 9.4% versus 5.5%.

In a prospective analysis of 2,214 offspring (mean age 44 years; 1,150 women), heart failure developed in 90 offspring during a mean follow-up of 20 years. Of these 44 had ischemic and 46 had non-ischemic heart failure.

The age- and sex-adjusted 10-year incidence rates of heart failure were 2.72% for offspring with a heart-failure parent versus 1.62% for those with unaffected parents. This increase in risk persisted after multivariable adjustment (hazard ratio, 1.70; CI, 1.11 to 2.60).

Approximately 18% of the heart failure burden in the offspring was attributable to parental heart failure. "These findings underscore the contribution of familial factors to development of the condition," Dr. Vasan said.

Most participants with heart-failure parents were older and had higher values for blood pressure and body-mass index compared with participants with unaffected parents, the researchers noted. However, they said, the associations remained even after risk-factor-adjusted analysis.

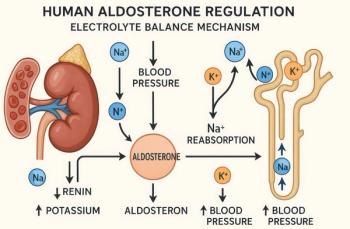

Discussing several mechanisms that may explain the link, the researchers said that the transmission of genetic factors may lead to maladaptive responses to biologic or environmental stresses. Also, the occurrence of both systolic and diastolic heart failure in the offspring suggests that altered diastolic function, increased vascular stiffness, and a propensity for sodium retention may be contributory mechanisms.

Finally, they suggested that there may be a familial aggregation of unidentified genetic, environmental, behavioral, and life-style-related factors.

The strengths of this study, the researchers pointed out, was the use of a community-based sample, and other factors, including the routine ascertainment of risk factors and collection of echocardiographic data, as well as the study's prospective design averting potential recall bias.

On the other hand, they said, because of the small number of affected offspring, it was not possible to evaluate the effect of having one or two affected parents or of having an affected mother versus an affected father. They also pointed out that because the sample was exclusively white, the generalizability of the findings to other races or ethnic groups is limited.

"Our demonstration of an increase familial risk of heart failure suggests, but does not establish, a causal relation of genetic factors to the disease process," the investigators wrote, citing the need for studies to "to examine the genetic underpinnings of this complex disease."

"Our data emphasize the contribution of familial factors to the heart-failure burden in the community," Dr. Vasan said. Provided that parental occurrence of heart failure can be reliably ascertained as part of a family history, this information would facilitate early identification of persons at risk for heart failure, he said.

Newsletter

Enhance your clinical practice with the Patient Care newsletter, offering the latest evidence-based guidelines, diagnostic insights, and treatment strategies for primary care physicians.