Filling the Knowledge Gaps in Iron Deficiency: 3 Questions

Questions about this common problem abound in primary care. Stop here for some basic answers.

Our world is populated with a staggering 2 billion people who are iron deficient, and iron deficiency anemia is the most common anemia worldwide. In primary care, questions abound regarding selected aspects of the diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency.

Let’s look at 3 of them:

1. Iron deficiency as a consequence of GI blood loss is well known. With colonoscopy, upper GI endoscopy, and capsule studies, bleeding sites can be identified and treated. How about some other causes we may not think about often enough?

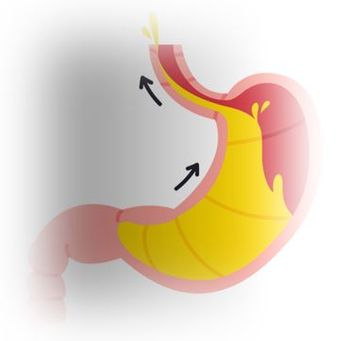

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is becoming a common cause of iron deficiency, with and without anemia.1 By its anatomic nature, the bariatric surgery removes iron absorptive sites from digestive processes and increases gastric pH, which also decreases iron absorption. Iron deficiency will develop in 45% of patients in this group.

Helicobacter pylori can compete for iron in the gut; reduce the bioavailability of vitamin C, which helps increase iron absorption; and cause iron loss through bleeding.1 When a patient is iron deficient and a site for bleeding cannot be found, do not forget celiac disease.

2. What is the best test to make a diagnosis of iron deficiency?

A serum ferritin level below 30 ug/L is the most sensitive and specific test for iron deficiency.1 Although hepcidin, a peptide that is an acute phase reactant, may become a helpful test in the future, it is not ready for prime time as of yet. Making a diagnosis of iron deficiency during inflammatory states is still difficult today because ferritin itself is an acute phase reactant.

3. When do we switch from oral to parenteral iron?

Remember, the new formulations do not have the prohibitive risks for anaphylaxis like the old iron dextran varieties did. Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia promotes nearly constant GI tract bleeding. To keep up with iron losses, parenteral iron may be necessary.

In patients with ulcerative colitis, oral iron may not be effective and may actually increase colonic inflammation. That is another clinical indication for parenteral therapy. Dialysis patients should receive their iron supplementation by parenteral administration.

Preliminary studies have suggested that parenteral as opposed to oral iron in patients with iron deficient heart failure may lead to fewer hospitalizations and a better quality of life. More studies in this regard are needed.

For a long time, I was taught that an increase in red cell distribution width (RDW), a measure of variability in red cell size (more variability equals anisocytosis), can differentiate iron deficiency from other microcytic anemias, like thalassemia. An increased RDW is not reliable enough to be used in this context.

Take-aways:

• In addition to GI blood loss, causes of iron deficiency include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery and Helicobacter pylori.

• The most sensitive and specific test for iron deficiency is a serum ferritin level below 30 ug/L.

• In patients with iron deficient heart failure, parenteral iron may lead to fewer hospitalizations and a better quality of life.

References:

1. Camaschella C.

Newsletter

Enhance your clinical practice with the Patient Care newsletter, offering the latest evidence-based guidelines, diagnostic insights, and treatment strategies for primary care physicians.