The Differential for Abdominal Pain: Go Broad

At least one-fifth of patients with abdominal pain may present in atypical fashion. A session at ACG 2015 stressed how essential it is to keep a broad differential.

Primary care physicians are inundated with complaints of abdominal pain-it’s a daily-dozen CC on any given clinic day. In many cases, an exam is unremarkable and reassurance is the best Rx. In other cases, it’s not so simple.

That was the key take-home message in the presentation at ACG 2015 titled “It Never seems to End: The ‘Work-up’ of the Chronicities-Chronic Abdominal Pain,” given by Dr Lawrence Schiller, clinical professor, Texas A&M Dallas campus; program director, gastroenterology fellowship, Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas. Pay attention to details--they don't usually disappoint.

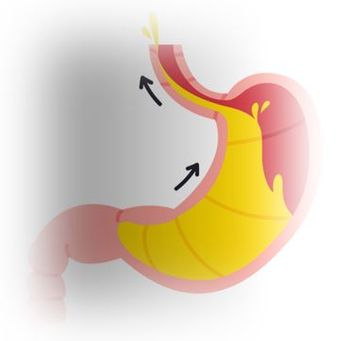

Pain is the normal response to injured tissue and can be the result of inflammation (eg, Crohn disease), obstruction (gallstones), inadequate blood flow (mesenteric ischemia), or infection (urinary tract infection) to name a few causes. The myriad possible intraabdominal, abdominal wall, and extraabdominal sources (such as referred pain from pneumonia, costochondritis, pleurisy, acute coronary syndrome) force an expanded differential and history remains the key. The quality of the pain, its acuity, location, and its relation to food intake or bowel movements all provide necessary clu es.When the pain is diffuse, it tends to be visceral.

Dr Schiller noted in his presentation that any one particular feature of abdominal pain is at best 80% sensitive or specific. At least one-fifth of patients may present in atypical fashion. In addition, a careful review of systems and physical exam provide essential information as well-such as organ enlargement, absence of bowel sounds, or abdominal distention. The sex of the patient adds additional complexity as normal pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, salpingitis, and pelvic floor dysfunction must also be considered in women.

The initial evaluation can be supported by laboratory results, endoscopy, cultures, or imaging. However, these results can be falsely negative. It is easy to fall back on functional abdominal pain (irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia for instance) when testing is negative. Doing so can lead to delays in diagnosis and therapy.

When a patient does not respond to treatment or does not fall within the diagnostic criteria for a functional disorder, the diagnosis must be reviewed and reconsidered. Has something been overlooked?

One of the most frequently missed etiologies for abdominal pain is the abdominal wall itself. Cause of abdominal wall pain, usually focal and limited to smaller regions, can go unrecognized. Potential causes such as port site pain, nerve entrapment, abdominal hernias, or fibromyalgia should be considered. Burning pain that follows a dermatome or particular nerve distribution should add thoracic spine pathology or shingles/post herpetic neuralgia as potential etiologies. Moreover, neuropathic pain is usually constant and does not cross the midline. Edges of the rectus sheath or the lower abdominal quadrants that are traversed by the ileohypogastric or ileoinguinal nerves can be locations for nerve entrapment. Changes in posture or tensing of the abdominal wall leading to abdominal pain (Carnett’s sign) are additional clues to these particular pathologies. Injecting the site with local anesthetic in the clinic setting can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Other rare syndromes such as angioedema (C1 esterase deficiency), porphyrias, lead poisoning, and familial Mediterranean fever should be entertained in the right clinical context-especially if typical diagnoses are excluded.

Keeping a broad differential, taking an extensive history and review of systems, and identifying key physical exam findings-then using these inexpensive, initial tools to direct diagnostic testing-can go a long way toward finding the source of your patient’s abdominal pain, especially when it is atypical or rare.

References:

Schiller LR. It Never seems to End: The “Work-up” of the Chronicities-Abdominal Pain. Presentation at: 2015 American College of Gastroenterology Scientific Session; October 18, 2015; Honolulu, Hawaii

Newsletter

Enhance your clinical practice with the Patient Care newsletter, offering the latest evidence-based guidelines, diagnostic insights, and treatment strategies for primary care physicians.