Curbing Antibiotics Tied to Britain's Drop in C.Diff

"Deep cleans" of UK hospitals was not the key to curtailing C diff infection; restricting use of one specific antibiotic was.

Limiting fluoroquinolones urged as control cornerstone

Restricting the use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics was more effective than measures such as "deep cleans" of hospitals in reducing the incidence of Clostridium difficile (C. diff) in Oxfordshire and Leeds, England, researchers reported.

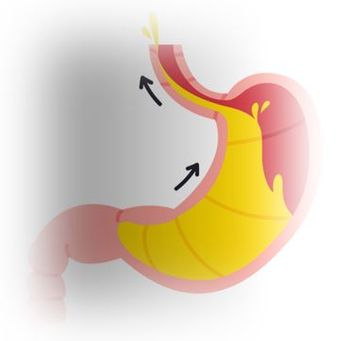

Antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin killed non-resistant C. diff bugs in the gut, enabling drug-resistant C. diffi bugs to thrive and inviting the rapid growth of resistant C. difficile, according to

National prescribing of fluoroquinolone and cephalosporin was highly correlated with incidence of C. diff infections (cross-correlations >0.88), by contrast with total antibiotic prescribing (cross-correlations <0.59) by 2006, they wrote in

In addition, a decline in C. diff infections in Oxfordshire was linked to the elimination of fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates, with the numbers decreasing from 67% in September 2006 to 3% in February 2013 (aIRR 0.52, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.56, P<.0001).

Crook explained that the study "shows that the C. difficile epidemic was an unintended consequence of intensive use of an antibiotic class, fluoroquinolones, and control was achieved by specifically reducing use of this antibiotic class, because only the C. difficile bugs that were resistant to fluoroquinolones went away."

"Reducing the type of antibiotics like ciprofloxacin was, therefore, the best way of stopping this national epidemic of C. difficile and routine, expensive deep cleaning was unnecessary," he said.

Said co-author

The researchers compared 1998-2014 national antimicrobial prescribing data for hospitals and the community (

Using whole genome sequencing, they conducted genetic analysis on more than 4,000 C. diff bugs to work out which antibiotics each bug was resistant to. Genotype and fluoroquinolone susceptibility were determined from whole genome sequences.

The incidence of C. diff infections due to fluoroquinolone-resistant and fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates was estimated using negative-binomial regression, both overall and per genotype.

Crook's group reported that inappropriate and widespread prescribing of antibiotics, not unclean hospitals, were responsible for the C. diff epidemic in Oxfordshire and Leeds, emphasizing the need to correctly use antibiotics.

Despite the implementation of comprehensive infection prevention and control measures, like better handwashing and hospital cleaning, the number of bugs that were transmitted between people in hospitals did not change.

Analysis of multiple whole genome sequence datasets found that cases of C. diff fell only when fluoroquinolone use was restricted and used in a targeted way as part of a multifaceted effort to control the outbreak.

Crook's group also noted significant declines in inferred secondary (transmitted) cases caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates with or without hospital contact versus no change in either group of cases caused by fluoroquinolone-susceptible isolates.

C. diff infections caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates declined in four distinct genotypes, the authors reported. The regions of phylogenies containing fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates were short-branched and geographically structured.

In contrast, the smaller number of cases caused by C. diff bugs that were not resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics remained the same. Incidence of these non-resistant bugs did not increase due to patients being given the antibiotic and were not affected when it was restricted, the authors reported.

They noted that understanding fluoroquinolone may be key to controlling C. diff outbreaks in the U.K. and worldwide. "These findings are of international importance because other regions such as North America, where fluoroquinolone prescribing remains unrestricted, still suffer from epidemic numbers of C. difficile infections."

"Similar C. diff bugs that affected the U.K. have spread around the world, and so it is plausible that targeted antibiotic control could help achieve large reductions in C. diff infections in other countries," Wilcox noted.

The study was funded by the U.K. Clinical Research Collaboration (Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, National Institute for Health Research), NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Healthcare Associated Infections and Antibiotic Resistance, University of Oxford in partnership with Leeds University and Public Health England, NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Modelling Methodology, Imperial College London in partnership with Public Health England, and the Health Innovation Challenge Fund.

Reviewed by

This article was first published on

Newsletter

Enhance your clinical practice with the Patient Care newsletter, offering the latest evidence-based guidelines, diagnostic insights, and treatment strategies for primary care physicians.